Press

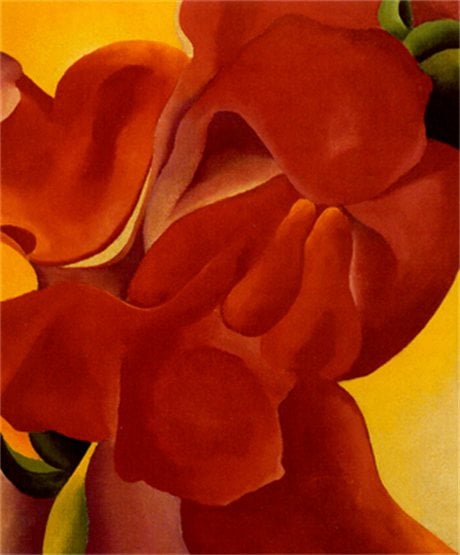

Red Canna by Georgia O'Keeffe

Red Canna by Georgia O'KeeffeMy Favourite Painting

Country LifeRed Canna by Georgia O’Keeffe

Sculptor Helaine Blumenfeld comments on Red Canna

Georgia 0’Keeffe’s paintings of flowers have deeply affected and profoundly influenced me from my childhood. This one captures the intensity and brilliance of a hot day in summer. It suggests transcendence into a realm that lies beyond substance; it is poetic and elusive; it is joyful. Ultimately, it is mysterious and visionary. The abstract image reflects O’Keeffe’s desire to capture the “essence” and to reveal a multitude of figurative references that she disguises that she disguises with transparent layers. She takes serious risks with colour and challenges visual harmony in order to stimulate the viewer to look beyond the parameters, to question what they see. Having first experienced this painting many years ago I often find myself revisiting it in my mind, both on dark days when I feel the need for intense light and renewal and, in celebratory moments when I want to share my optimism and sense of possibility.

Art critic John McEwen comments on Red Canna

GEORGIA O‘KEEFFE‘S father was a Wisconsin dairy farmer of Irish descent, her mother the daughter of a Hungarian count who came to America in 1848. At 10, she decided to be an artist was given her first art lessons. She art student in Chicago and New York and subsequently forsook fine art to work as a commercial artist. Her childhood ambition was reignited by the ideas of the New York-based teacher and painter Arthur Wesley Dow. Dow saw music as the key to the fine arts, painting a matter of visual music — the harmonising of line, form and colour.

O’Keeffe’s first show was in 1916, at the photographer and New York art dealer Alfred Stieglitz’s avant-garde 291 Gallery. Stieglitz had a wife and child and was 23 years older than O’Keeffe, but they fell in love and married in 1924. Despite infidelities and leading often separate lives. they stayed married until his death in 1946. O’Keeffe died the died the grand dame of American painting.

Her breakthrough exhibition came in 1923. The painter Marsden Hartley introduced the show’s brochure extolling her pictures as ‘shameless private documents [with an] unqualified nakedness of statement.’

She said: ‘Nobody sees a flower, really; it is so small. We haven’t time, and to see takes time — like to have a friend takes time.’

During the harrowing pre-marital summer of 1923, she wrote to Stieglitz: ‘All that I am goes to you’ and, in another letter: ‘It’s living that matters — there can be no worthwhile painting if there is no equilibrium.’