Press

Helaine Blumenfeld: ‘Beauty has no real meaning any more’

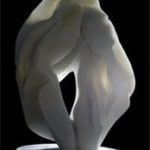

Studio InternationalThe sculptor talks about her ideas of beauty and pain, and how she learned to express these through a visual language

A professor of philosophy before turning to sculpture as a way to express her dreams and emotions, Helaine Blumenfeld (b. 1942, New York) has been hailed as the successor to Henry Moore. Her translucent marble works and flowing bronzes take the viewer’s breath away. Blumenfeld was the first woman to be awarded the International Sculpture Prize Pietrasanta e la Versilia nel Mondo in 2007 and was the vice-president of the Royal British Society of Sculptors in 2004-09. With an exhibition of her works currently on show at Hignell Gallery in Mayfair, she invited Studio International to visit her at her home and studio in Cambridgeshire.

Anna McNay: Can we start by talking a little about your current exhibition at Hignell Gallery? The title is Hard Beauty. How is one to understand this concept?

Helaine Blumenfeld: Well, I have to start by saying that I think that so much of our language has become trivialised and overused. You would never dream of calling a show “Beauty”. Beauty has no real meaning any more. We don’t know what beauty is. I think beauty has been knocked off its pedestal and we don’t really understand why. After Adorno argued that it would be almost criminal to write a poem after Auschwitz, there was a movement among artists to feel that their responsibility wasn’t to do something beautiful, that one had to deal with the horror, the terror, the tragedy of the life around us. But I believe that the only way of healing any of that is through beauty, and that it’s a complete misunderstanding of beauty to think that it doesn’t deal with pain. The greatest paintings, the most beautiful paintings in the history of art, are all of the crucifixion, and some of them are terrifying. Kierkegaard argued that art begins with a scream but if the artist doesn’t transform what they’re doing into music, it isn’t a work of art, and I think that’s true in music, I think it’s true in the visual arts, I think it’s true with theatre, that it is an effort to bring together and to explore pain or deep, deep emotion. So, I think that, at a very basic level, beauty is about our deepest feelings and a way of expressing something that is almost inexpressible.

Hard Beauty refers both to the substance matter – in my case, to the materials I use, which are very hard – to the process that I have gone through to learn to carve and to create this work, and to the creative process itself, which is not spontaneous and easy. That’s a myth. Almost any artists I admire, if I look at their lives, they were not easy lives; they were lives where you’re living as close to your own emotions as possible to produce something which is really unique. I didn’t name the show, but it seems such an appropriate name.

AMc: Are there aesthetic values in your idea of beauty as well?

HB: The Greek view of beauty had to do with a kind of balance or symmetry, or all the elements and proportions being right, and all of those things are important to me. I don’t really believe that it’s necessary to distort, and I believe it’s very important for the viewer to be part of that process of looking.

AMc: You’ve mentioned a couple of philosophers already, and I know you came into art after having been a professor of philosophy. What led to the career change?

HB: As a child, I had dreams or visions that could never be described. I’d wake up and I’d talk about them and everybody would look at me as though I were an idiot. I realised that I didn’t have the language to describe what I was seeing. It took me a very long time, and a search through philosophy and language, before I realised that ordinary language doesn’t have the capacity to express dreams or something that is beyond language. Later, when I was with my husband in Naples, I saw a case of Cycladic sculptures and each one told such a story. If you were going to write an essay about the person those features represented, you wouldn’t get it, but you could look at the sculptures and read into them everything you knew about people, every person you’ve known, and pull out what that little head represented, and it seemed to me, suddenly, that there was a visual language, I just had never tapped into it. I’d never worked with it.

Some months later, my husband [Yorick Blumenfeld] was offered a job in Paris. I didn’t really speak French, and he asked me what I was going to do. I said I thought I’d like to study sculpture. So I got some clay and made some tiny models in the kitchen of our flat. He photographed them – he’s a great photographer. His father was Erwin Blumenfeld [the famous fashion photographer]. He took some beautiful pictures, and made me a portfolio. In those days, you didn’t need to say where you’d studied or anything, so I went to Palais des Beaux-Arts and was accepted right away. A student I met there took me to lunch and said he thought I’d be better off at L’Académie de la Grande Chaumière where Ossip Zadkine [the Russian cubist sculptor] used to teach. So we went over there – I still had my portfolio with me – and I was accepted there instantly and started the next day. It was lovely, near Boulevard Montparnasse, a wonderful area. I didn’t really know anything about sculpture; I hadn’t been an enthusiast at all, but I looked up who Zadkine was and one day he came in when I wasn’t there and saw the clay things I was doing and said: “Oh, send this young man in to see me on Sunday.” He used to hold salons. I was very shy and didn’t think I could do it, but my husband said: “No, no, you’ve got to go.” Zadkine was quite a small, wiry person with a very red face and lots of white hair. He jumped up when I walked in and said: “Who are you? Qui est?” I was so embarrassed. I said who I was, and he said: “Oh, they told me you were a man, but sit down, sit down.” And he was fascinated. He was very thrilled to have me and, by the end of the afternoon, he asked if I would like to work in his atelier. It turned out that the main thing he wanted was somebody there in the morning, when he came in, to keep a discipline. My main thing to do was to be there at 8.30 in the morning and stay until 5pm. I don’t think I learned a lot. He wasn’t a teacher. I think I asked too many questions in the beginning and he would always just say: “Meh”, like “I don’t know.” Because I wasn’t used to working in clay, whenever I had a head on a figure, it always broke off because the neck had to be wrapped because it would dry much quicker than the rest of the model. Even if you put a bag around everything else, the neck had to be wetter and no one told me that, so the neck always broke off. Nor did he tell me to make an armature. I never learned it and it just seemed nice not to do it and, later, I wouldn’t dream of it because that would really inhibit where I was going. What I did learn was huge concentration and absorption in what you’re doing. Nothing else exists. He had complete communication between what was going on within him and his hands. There were lots of difficult moments. I didn’t please him, but it was never because of the work I was doing; it might have been because I came in wearing lipstick and he would tell me I was dressed too nicely. He was very stern.

AMc: Were you working figuratively at that point?

HB: Actually, no, never. I never really worked figuratively, always abstracted. I never really questioned that. I felt enormous certainty. I felt happy, really happy. There was such an ability to translate my emotional state into what I was doing. When we moved flats and a few pieces broke, I knew I’d never do them again. There was a sense of wonderment. Oh, my God, what have I done? I don’t think I’d ever been a happy person before that. I was finding a voice that was expressing my dreams. I was finally able to go beyond language and communicate something that seemed important.

AMc: There’s a lot of movement in your sculptures, as well.

HB: That took a long time to develop and the movement came, really, from going to the museum and being completely knocked out by a sculpture by Raymond Duchamp-Villon, the brother of Marcel Duchamp. It’s called Horse. It’s a great sculpture. You actually see it moving. And then I became interested also in the futurists, who are showing motion, but in every case the motion was physical, and I think my motion is the motion where it’s moving from one state of being, fleetingly, to another. I don’t think the futurists were interested in that: they were interested in the physicality of that movement.

AMc: How important is touch to you and your work? I was really surprised in the gallery that I was invited to touch the sculptures, which is unusual.

HB: Touch is very important. Touch is what distinguishes sculpture from anything else and it’s how you feel it. Early on, I had a show in New York and the broadcaster and talkshow host Charlie Rose decided to bring people from the LightHouse for the Blind to the exhibition. The idea was that I would talk about the work without anybody there and then the people would come in and they would say what they felt from touch. What they said was so close to what I had said that it seemed like I had told them in advance. It was amazing. I think art talk ruins sculpture for people, and paintings. You’re told what it’s about. Georgia O’Keeffe really felt she was under the pressure of the myth of eroticism but, as you pointed out in your review, a flower is a flower. I’ve suffered from some of that as well, but I do think eroticism is an element. Sensuality is a strong element in my work, but when Salisbury cathedral asked me to do a show because it thought my work was so spiritual, I felt completely thrilled, because it is spiritual as well. We don’t have to make these sharp distinctions – spirituality and sensuality are on a continuum.

AMc: You began sculpting in 1962, but it was not until 1978 that you first went to Pietrasanta and began working with marble. What led you there and how difficult was to be accepted in such a male environment?

HB: It was a little earlier, actually – 1974 probably. I ended up going there because a collector had bought a work of mine, which was cast in England, and we felt the casting was terrible. The American gallery that I was showing with was called Bonino and they had a branch in Italy and represented a great sculptor called Alicia Penalba. Alicia worked and lived in Pietrasanta and they said I should go and talk to her about the foundries there. I showed her the models that I wanted her to cast and she’s the one who said the work should really be in marble. I’d worked with marble, but only as an exercise. I certainly wasn’t a carver at all, but she introduced me to Studio Sem and Sem Ghelardini. When the church changed its dictates and there was no longer the possibility of having marble sculptures remade every year, because the money was gone, all the marble studios in Pietrasanta started to suffer because they’d been surviving on church sculpture for so many centuries. Sem Ghelardini was one of the people who got the idea to start working for sculptors. The artisans, at first, were very against it. They were so used to doing very, very figurative work, very detailed church work, that the idea of doing work for an artist that might be abstract appalled them. Jean Arp brought work there, and Henry Moore, and a number of much more abstract sculptors started to come.

So, there were now a number of studios that you could work at and, in most cases, it was the artisans doing the work. You left the model for them to make. But I was determined to learn to carve and to do it properly and that was hard. That was very hard because that wasn’t what women did. There were a number of women who did leave work there, but mostly, even if they left it, they didn’t follow it through, and I think that was a breakthrough for me on a lot of levels because I don’t think anything changes in your work unless you change, unless you take personal risks. I’d had a show in New York. It had been a great success, but nothing was changing. I could see I was doing the same work again. I felt really attracted to marble, so decided to try working there for a few weeks at a time. I had two small sons at home, but my husband is a writer, so he was always there and his mother lived nearby, too. I had tried working from home, going to the studio and locking the door, but it wasn’t good enough. I was preoccupied with the family and very dissatisfied. My elder son felt that it was very hard with me around. I was grumpy. When I went to work in Pietrasanta, even briefly, I’d be in a better mood when I came back.

AMc: So you split your time and were in Italy for two weeks and here in Cambridge for two weeks?

HB: Yes, and it was very tough. It was very hard losing security and stability and the pattern, the ritual of life. It affected my work. Suddenly, it just came off the base. My works had no bottom any more, no fixed way of putting them, and I realised that that complete lack of security and stability had changed me. I was now translating that into what I was doing. It was a huge breakthrough. The first years working in that way were very painful and I think the work maybe shows that – there is a lot of rupture, a lot of cracks, a lot of fragmentation. Gradually, things came back together into single pieces again. I’m very interested in how little has been written about that transition of women from being involved in family to trying to break out of that. Not one woman that I know in Pietrasanta has a family and a husband and children. It’s really, really difficult to manage that because so much emotion goes into what you’re doing.

AMc: During the two weeks that you then came back here, did you totally switch off from your work?

HB: No, I still worked, but I was able to follow the children’s school routine. Someone recently asked my son what was the hardest thing about his mother coming and going, and he said, well, the hardest was that when she came back, she was a perfect mother. She just did everything; she was incredible. She would never tell us when she was going to leave and suddenly she would just go. Of course, I felt that if I named the day when I’d be gone, they’d be waiting for me to leave all the time. So, the night before, I’d say, I’m going tomorrow, and my son said they really suffered from that. I didn’t realise at the time. Nor did I realise that by overcompensating in the time I was here, I was making it harder.

AMc: Would you change any of that now, looking back and having heard what your sons have said?

HB: I think I would. But I think I can’t. I don’t know. I’ve been making a film recently and, in one session, my son Remy interviewed me himself, because he’s a film-maker, and because he knows the questions to ask. He asked them and I just burst into tears. He didn’t ask if I would do things differently; he asked why I went at all. I had no answer, but I think at the time I did it, and probably would again, because I felt I had something important to communicate, really, that needed that space. If I had stayed here, my whole life would have broken up. I wasn’t enjoying parenting. I would wake up at five in the morning to come down and work before everyone else would wake up. I was wearing myself out, and nobody felt happy with me and I didn’t feel happy. So, I think, probably, although I can look back and say I wouldn’t, if I didn’t, something else would have happened. The drive, the passion, was just too great. In the film, Remy was asked, looking back, how did he feel about my career, and he said, if I had given up, if I at some point just said, OK, it’s not worth it, he would be very bitter, but because I went on and I’ve been so successful, not in terms of being known or selling, but successful in how he sees the work, he felt wonderful about it and that he had been part of it. I just put this piece up at Canary Wharf last week and Remy, who is quite critical of me in many ways, said he’d never been so proud. That made me feel very good. So probably I wouldn’t do anything differently.

AMc: You’ve just mentioned Fortuna, the piece at Canary Wharf. Can you say a bit about this work and what it is about?

HB: It’s about the human condition – pulling and pushing and space and turbulence. But I became a sculptor so as not to have to tell you in words what that sculpture’s about. I can’t do it.

AMc: How do you feel about doing interviews and having to talk about your work when the whole point of the work is that you don’t have the words?

HB: I think if someone has seen the work, like you have, we can talk about it. But if someone comes – and this has happened – and they really haven’t looked at anything, they haven’t thought about it and they just want me to talk about my work, I just say: “Awfully sorry, I can’t do this interview.” You’ve got to start with some feeling about it. Sometimes I say to the person: “You talk to me about my work. What do you see in it?” But, no, I think that the work has got to speak for itself and it’s got to affect people and it’s got to go on doing that. The wonderful thing is you go to a museum and you see amazing things and you often have no idea who made them because the artist isn’t what’s really important. So much of what we see from the Greek period, we don’t know the names of the sculptors. It really isn’t important. Equally, enormous talent isn’t as important as being able to step back from what you’ve done and see it and change it – and reject it.

AMc: I find all of your work beautiful, but the marble pieces especially have some exceptional quality for which I also struggle to find the words. There is a light that comes from within and a contrast in what is known (that they are made of a cold, hard material) and what is perceived (namely that they are soft, flowing and undulating).

HB: Light really is a part of the sculpture. I believe we have a soul and that it’s not a religious feature, not tangible and not describable, but it’s something there, and it’s there as a translucency, a transparency, as an illumination. It’s what lights us up. You see five people in a crowd and one of them just jumps out at you. It’s because they’re closer to that inner energy. I was very good friends with [the molecular biologist] Francis Crick and we had tremendous arguments because he didn’t believe there was anything called a soul or that you could find it in matter, but that’s the whole point – it isn’t matter. It’s art material. As a child, I saw clouds all the time, and the images I saw were shapes that moved and had light coming through them. I’ve done some things in glass as well but, somehow, with glass, the light comes through too quickly. What I love about marble is how, as it gets darker, you still have some parts of the form that have the light coming through. You don’t get that in bronze. The shapes have to do it for you instead.

AMc: The surfaces of your works are complex – although the marble is largely smooth, there are sections where you have worked into it or created a rough, seemingly unfinished area, a variegated texture showing the trace of the artist’s hand.

HB: Also, another thing I developed was the idea of shattering the top. I like to think of them as almost a drawing in space but then, instead of having a smooth line, shattering it so that you have this feeling of emerging. I think it has to do with how we are as human beings. We’re not finished. Very early on, when I started to do the very rough inside, it had to do with this feeling that, as human beings, we cover ourselves up so that we’re not visible as the person we are, but the energy inside is moving forward and it’s breaking that shell so that, if we’re alive, if we’re active, if we’re feeling, that shell will shatter and you’ll see through it to the real person. People feel it, as you say, as something unfinished or as a kind of energy.

AMc: Can you say a bit about the process of making a new work? Do you make sketches or models? Do you know what you want the finished piece to look like before you begin?

HB: I always start with a clay model. I think that’s my drawing, really. And that’s done in almost a state of … how shall I describe it? I know Francis Bacon said he always had to begin by either being completely drunk or drugged or both so that he’d almost lose his consciousness. I think I start in a similar state, but without alcohol or drugs. I can go 20 hours working and I never look at what I’m doing until it’s reached a stage where I know what it is. I feel it. And then I’ll leave it and I’ll come back and look at it later on. If I leave and it isn’t yet finished and it’s in clay and I cover it, when I come back, I don’t think there’s any way I could tell you what was under that cloth. I have no idea. I imagine it in my mind as something wonderful, but I couldn’t tell you what it was. I’m often quite shocked. I have no recollection.

AMc: So you’re working in this state and you’re not looking, you’re just working with your hands …

HB: Yes.

AMc: … feeling it and translating the feelings?

HB: Yes. And because I have no armature, no beginning, I don’t know where I’m going. I used to find a lot of the pieces would just collapse and there was nothing there, but I learned, after a very long time, to work much smaller because once I’ve done it and I’m happy with it at that scale, I can have an armature, I can enlarge it, because spontaneity isn’t involved in the enlarging.

AMc: How long would you typically spend on one of your clay models?

HB: You can’t spend too long. It’s like baking a cake: you can’t take hours. Very rarely do I work on the initial model for more than three weeks. But then I get a cast of it in plaster. I have someone I’ve worked with for 30 years to do that. He knows how to do these complex pieces like nobody else does. Then, when it’s in plaster, I might work on it for a year, adding and taking away and finishing and then rejecting it. I was working on a large piece that someone had commissioned me to do. I have someone who does really big enlargements for me and he was making it to measure and I came back from England to see it and to start working on it myself, and, at that point, I just said: “No, I’m sorry, I’ll pay everything it’s cost to get it to this state, but it’s a terrible piece!” Everyone was really unhappy, especially the enlarger, who loved it. The person who commissioned it loved it, too, but I could see it wasn’t good. It wasn’t what I needed it to be. It’s visceral. It’s intuitive.

AMc: When you’re working on the plaster forms, are you looking at them then?

HB: Yes, then I’m being very critical.

AMc: So there is some rational, critical thought coming in at that point.

HB: Yes, absolutely. I have two eyes. I have a completely intuitive, emotional initial creative way, which isn’t really looking in a sense, and then the critical eye that comes in and is brutal and makes those adjustments or decisions.

AMc: And it’s essential for the work that you have those two voices?

HB: Yes, it is. That’s what I was saying, that if you don’t have the ability to stand back and see it as an object, no longer as your subject, then I think your work will fail – and I make that judgment for anybody. It’s perhaps not a fair judgment to make, but I think you have to be able to separate yourself from it and see it and say: “That’s too heavy, that’s too thick, there’s not enough movement.” Even if no one else thinks that.

AMc: Where does the element of risk come into your work, because I know that’s something you’ve spoken about as being important as well?

HB: Oh, it comes in all the time. The condition, I think, of being a sculptor is a risk, that you can work for weeks or months and if you really are just saying if you like it or not, if it’s good or not, you might do nothing. You might do it and nobody else likes it. You might do it and nobody has any sense of what it’s about or it doesn’t communicate. If it only communicates to you, it’s failing totally. The risk of putting so much of who you are and what you feel into it and working in that way – it’s like going into a dream world. Maybe you don’t come out of it. Now it’s time to go back to do something and you’re still there, but you’ve opened up things that are painful or that can’t be resolved. It’s a huge risk living on that edge of your own creativity. It’s also a risk that you could have come on a day when I couldn’t talk to you because I just was not there. You can’t count on yourself in that way. You’ve got to allow yourself that freedom to move in and out of your own cycle. For example, I’ve got some new clay that I want to start working with, but I knew you were coming, so this whole week I thought I don’t want to start a new piece because, when I do, I don’t want to be interrupted. I don’t want to talk, I don’t want to think, I want to be free to just do that. As you see, getting away and working somewhere else was so important because I’d almost never have had that freedom here, with children and a family, to just immerse myself in what I was doing.

AMc: Do you still split your time now, even though the children have grown up?

HB: No. Well, I still go back and forth to Italy, yes. For almost 25 years, my husband and family never came with me because I thought it was not a place for them. I created a certain persona, quite a hard person, quite ruthless about doing what I had to do, and all I would need was my children and husband there and I would no longer be that Elena, I’d be Helaine.

AMc: You were the first woman to be awarded the International Sculpture Prize Pietrasanta e la Versilia nel Mondo in 2007. What did that mean for you?

HB: I was very honoured by that because it was such a closed circle. Only men had ever got it and no woman was ever even considered. I was completely shocked. I got a phone call in the December after the committee had met and, I’ll never forget this, they told me I had won and that I had to get the prize on a certain day and I just thought someone was joking. Of course, I knew about the prize – it was a big event every year. The winning artist has an exhibition throughout the whole city and gets the keys to the city. I said: “Who is this?” They were speaking in Italian. I really thought it was a joke. But, anyway, I was very thrilled. It was a real breakthrough.

AMc: Have you seen things change there over the 25 years that you’ve been going?

HB: Oh, my goodness, things have changed! I think a lot of people see me as a role model because now there are more women working in Pietrasanta than there are men and they are working harder, and it’s not at all the sort of scene it was. Also, sadly, the studios have had to move out of Pietrasanta because of pollution. The bronze foundries are doing very well and have a lot of activity, much more than they did in the beginning, and it’s now almost completely turned over to professional sculptors and students rather than church work. I’ve been very involved in the Royal Society of British Sculptors and I established a residency for them that allows a sculptor to come and work in marble and someone to work in bronze, and I mentor that programme. It would be good to have more of these. When I started, I was told that bronze and marble were out of date and, even now, one of the things that annoys me is that, whenever you hear talk about “the cutting edge”, it is never the cutting edge in marble or bronze, it’s always in some new material or papier-mache or whatever – not even in wood. But there would be no history of art if we didn’t see that the cutting edge is going to be pushing forward in marble and in bronze. I worked for years with someone who only carved roses so that I could learn to do the layering that I do. Every time I tried, the whole thing would break off, and I discovered you have to use a tiny drill. You go in with the drill under the surface and then you can go in with a chisel. If you go in with a chisel directly, the whole thing comes off. So, I began to do this as a technique, not a decorative technique for flowers, but a meaningful technique in terms of opening up and layering. The layering, I think, and the revealing the light have been things that were not done in sculpture before. I also worked with someone who did drapery and it was in doing the drapery that I began to see that by changing the drapery, so it wasn’t conventional drapery but fragments of drapery, I could start to go thinner and get the light coming through and changing what the drapery was like. I learned really through trial and error and by going to people who knew the technique, but for another purpose.

AMc: You mentioned your father-in-law, Erwin Blumenfeld, earlier on. He was the first person to photograph your work. Do you remember that occasion?

HB: Yes, I do. He was such a difficult person, so judgmental and so anti-art in many ways that I was quite afraid of him. On the other hand, I think his complete disdain for academia, which is what I was in at the time, also affected me. He had no respect whatsoever for academics. He’d never gone to university – he’d hardly finished school – but he was brilliant. He read everything and he really absorbed what he read and criticised it. Meeting Yorick and his family at such an early age really affected my idea of what was important and gave me that realisation that there was another path to what I wanted to achieve. It made me more receptive to seeing those sculptures and thinking that I could do that, too. So, when he came to Paris, I wouldn’t show him my studio at all. Yorick was working for Newsweek and he’d sometimes be working all night and my father-in-law and I, when he’d come to visit, would take long walks and he would talk to me about all kinds of things and always end up saying that he’d like to see what I was doing. I’d say: “No, I’m not ready.” When we moved to Vienna, I knew that was it, he was going to have to see things, and I was afraid I didn’t have enough work to show him. I was even putting together conceptual pieces that I could show him because I was very insecure. I knew that whatever he’d say was going to affect me enormously. We made a plan for him to come up to the top of this old palace we lived in, four storeys up, and he came in and he just looked around. He didn’t look very pleased or displeased, he just stumbled around and then he left. It seemed clear to me that he didn’t like anything and, because he liked me so much, he didn’t want to tell me. It was interesting because I was, on the one hand, demolished, but I also remembering thinking: “Well, I’m not there yet, this is just the beginning. I don’t think this is great either. He can’t see that I’m going to get there, but I know I will.” I went back to work on the piece I was doing. I’d been building something up and it was quite small and his apparent dismissal gave me the courage to take a lot more clay and I started making a much bigger piece. Then, it must have been an hour later, I heard him coming back up the stairs and he now had all his cameras with him and he’d brought a huge roll of white paper, which he rolled out saying: “Hold this! Do this!” I was amazed. It was wonderful.

AMc: So, he wasn’t dismissing your work at all?

HB: No, he thought I was immensely talented and he wanted to take photographs. He was very excited that I’d given up philosophy to make sculpture.

AMc: Do you think there has been any conversation at all between your work and his work? Some of the smooth curves and shapes of your sculptures might be seen to echo some of the female forms in his photographs.

HB: I think there’s enormous conversation. If you see his nudes with drapery, how they become so abstract, you don’t really see very many figurative nudes there. The idea that sensuality is about the subtlety of an image or the abstraction of the image or the feeling behind what you’re doing. I think he managed to have enormous sensitivity in what he was photographing. It wasn’t just fashion photography – that was not what really excited him – it was always the experimentation. He rarely distorted, although he did do a series of distorted images called Homage to Bacon, and Yorick brought them to Francis Bacon who said: “Oh, God, these are awful, I hate distortion!” He had no idea that it was what he was doing. My father-in-law would make 100 prints from a negative until he got the one that had exactly the balance of light and dark that he wanted, and I think that really striving for something more each time was something that he had that I admired very much and I think I followed.

• Hard Beauty is at the Hignell Gallery, London, until 27 November 2016