Press

Flight at Salisbury Cathedral

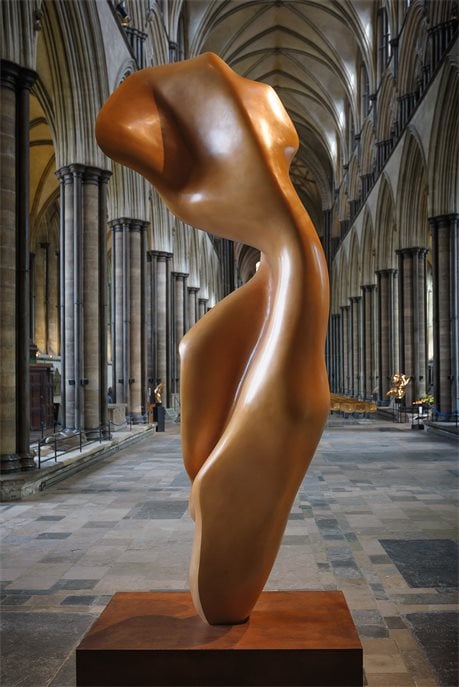

Flight at Salisbury CathedralOutward signs of inner light

Church TimesKaty Hounsell-Robert visits a Salisbury sculpture exhibition

“FOR ME,” Helaine Blumenfeld says, “sculpture has been a journey to try and reach beyond the physical, emotional, and cultural boundaries that limit our perception as well as our growith as spiritual beings. Through sculpture, I have tried to create a visual language that does not depend on words but on images for its impact.”

For 40 years, Blumenfeld has dedicated herself to following this challenging path in, as she says, “a world that no longer reveres beauty and spirituality.” She now has more than 65 works in public places and private collections all over the world. Until September, she has an exhibition at Salisbury Cathedral of 18 works in marble and bronze, sculpted over the years, 12 to be seen within the cathedral, and six spaced out on the surrounding green close.

Even as a child, she had sensed the limitation of words, and, after initially studying philosophy in the United States, where she was born, completing her Ph.D. at Oxford University in 1964, she finally came to the conclusion, when living in Paris with her new husband, that she need to work visually.

She began studying art at the Academie de la Grande Chaumiere, where her work was noticed by Ossip Zadkine, the renowned French sculptor of Russian Jewish descent, famous for blending cubism with figurative work, and for his The Destroyed City, inspired by the horror of the bombed city of Rotterdam. He took her under his wing. “He didn’t teach as such, but, as an apprentice, I was able to watch a great master at work – his focus, his egocentricity, which he expected of all his pupils.”

Her early exhibitions were mostly figurative portrayals of couples and family situations greatly influenced Henry Moore, Constantin Brancusi, and Jacob Epstein. She worked in bronze, which remains a favourite medium. “As an artist, I have sought to put into form the complexity, beauty, and mystery of the human spirit, known to us only in sudden glimpses. You can meet someone who seems to have an inner light, and you know they are a spiritual person. Highly polished bronze gives that light and shadow, complexity, ambiguity, and mystery.”

One of the first things you see in the cathedral nave, its polished golden bronze reflected in the constantly flowing baptismal pool, is Messenger of the Spirit, the sculpture that gives its name to the exhibition. It seems like Mercury or maybe an angel in full flight, going too fast for mortal eyes to see the exact shape.

Angels and the soul struggling to reach a more spiritual level and break out from its worldly strictures are themes of many of the works, as is the theme of needing and creating space. The titles of most of the pieces leave plenty of room for the imagination: Esprit, Mysteries, The Space Within, Shadow Figures, Angels, Souls.

Blumenfeld observes: “People say to me ‘You’re very difficult,’ but you have to give something of yourself, and then you come out with a sense you have discovered something about yourself. Each piece I create is message, and it’s the message, not the messenger, which is important, Art is a revelation, both for the artist who receives a vision and for the viewer to whom it is transmitted.”

But she willingly explains the inspiration behind the work and what she is trying to say, and is giving talks and workshops throughout the exhibition.

A modest and unassuming person, Blumenfeld says: My other medium is marble.” When her children were young, and she needed space and time to focus, she discovered Pietrasanta, in Tuscany, where Michelangelo lived and worked. She found that she could go there for short periods and be totally focused.

Here she tried her hand in the marble studios of Sem Ghelardini. Here, too, she patiently learned from an old man who had spent his whole life sculpting the fine folds of rose petals. She developed this technique, and symbolically uses fine carved folds and layers over her forms. “The layers convey what is preventing us from confronting reality. We grow from inside, but we create this shell around ourselves which stops us growing. It protects but also inhibits the energy of our spirit pushing out. The fragmentation in the layers is the inner self breaking out and growing.”

The pure white marble from quarries between Pietrasanta and Carrara is polished in the open air with fine sandpaper, and some of the fine carving has feeling of beautiful white decorative icing. In the north transept stand two pieces just touching with fragile-looking petals like a flower opening: Taking Risks – a slogan frequently used in the arts in France, and which Zadkine instilled in his pupils.

Just outside the entrance to the cathedral, looking very much like a chaotic pile of stones at a distance is the most beautiful piece of carved Macedonian marble, Creation. It is like the beginning of life, as though in a foetal position, waiting to spring out into the fullness of living. In its folds are tiny wings waiting to shake out and fly, and in every crevice delicate detailed carving: a piece many people passed by, but in which you could see something new every day.

Blumenfeld draws on Greek philosophy and mythology, and in the cloisters is Psyche, the beautiful mortal, who through many Herculean tasks, was granted immortality by the gods. Her polished bronze form is robed with detailed folds, but her face is unseen. Blumenfeld explains that Psyche was an earlier version of a marble Cleopatra who stands tall and magnificent on the west lawn, also shrouded in folds. She represents every woman, a sovereign in her own right, but trying to free her inner self.

Also in the cloisters is a touching marble of two slim upright shapes suggesting friends in harmony together. Blumenfeld calls it Shadow Figures, on the basis of the Platonic idea that we never really see a person: we see only the shadow that he or she casts, which changes all the time.

The Space Within on the West lawn shows three tall, tree-like shapes in muted-green, polished bronze, facing towards one other, separated by a space, and with their back like hollow trees. This was originally created in 2008 and enlarged for Salisbury. To accompany it, Blumenfeld had written: “Space for reflection, space for creativity, space for growth, space for renewal, space to discover who we are and how we relate, space for intimacy, space for sharing, space for the spirit to soar, without it we cannot survive as individuals or as societies.”

It is sad when people seem to think that the sculptures are too difficult to understand, and walk away. A little girl of five or six had no such inhibitions. She ran excitedly up to Ascent, a huge, muted-green, polished bronze, 3.35m high, thinking it was an elephant with flappy ears. Then she found a hollow at the back and explored in there. I think Blumenfeld, essentially a family woman, would have been delighted that the piece spoke on many levels.

On many levels, too, is the humble Bench, a beautiful, simple piece, cut into an irregular shape of marble and where one can sit and meditate on the other sculptures.

Of Jewish faith, Blumenfeld feels honoured and privileged to be showing at the cathedral. “To me,” she says, “it is a ‘sacred’ place of the spirit, accessible to people of every religion, and to non-believers as well.”

Dr Timothy Potts, former director of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge where there are several of her pieces, observes that she is “a force of nature, an extraordinary artist, and a great contributor beyond her work itself. She’s been an incredible advocate for public sculpture, for the arts and what they can do in communities, and the effect they can have on people.”

At Salisbury Cathedral and Close until 8 September