Press

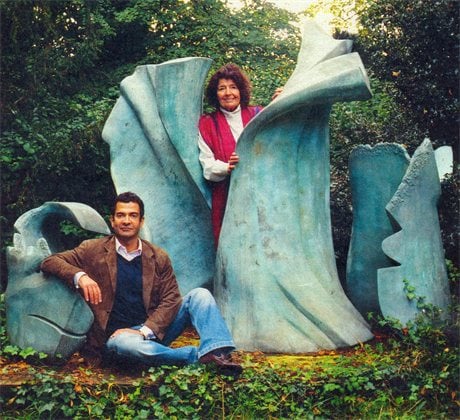

Helaine and Remy today

Helaine and Remy todayA mother and son who break the mould / Helaine Blumenfeld and her son Remy

The Sunday Times MagazineThe award-winning sculptor Helaine Blumenfeld, 63, is married to the writer Yorick Blumenfeld. She divides her time and work between Cambridge and Pietrasanta, Italy. The couple have two sons: Remy, 44, a TV producer, and Jared, 39, a director at San Francisco’s Department of the Environment. Remy has devised more than 50 television series, including You Can’t Fire Me I’m Famous and Gay, Straight or Taken. In 2001, he sold one of his production companies for a reported £10m. He lives in London and Kent with his partner, the photographer Henryk Hetflaisz.

REMY: As a kid I just wanted to blend in, but I felt Jewish and I felt gay, long before I even had a word for it. And then I had this eccentric mother. The clothes she wore were a huge embarrassment. Maybe other people thought she looked flamboyant, but to me she looked like a gypsy. She’d wear big pieces of jewellery and smock dresses and carry huge bags, and her hair was always a shock. She lived, and still does live, a parallel existence between here and Italy, where she sculpts. She always managed to be more eccentric than any of the other mothers. At my friends’ houses I ate fish and chips; when they came to mine, we had my mother’s Moroccan tagine and I felt so responsible for their experiences. Back then I thought: “Why can’t she be a bit more normal?” I’m sure she tried, but was never normal enough for me.

Yet all those things which were embarrassing about her then are the very things I now celebrate. She was a true earth mother – I don’t mean someone who bakes cakes and irons clothes, but someone very spiritual who is massively connected to the ground, who creates things out of the earth from stone and clay. My friends’ parents would rush round doing things with them, but that wasn’t my mother. We didn’t go to the park or zoo. I just remember conversations.

When she was there, she was completely present and she’d want to know everything. It was a very intense experience, and it still is. When I came down for breakfast my mother would say, “Tell me about your dreams,” and I grew up thinking that was entirely normal.

Until I was about 11 our relationship was pretty wonderful, and from 30 onwards it has been wonderful, but the time time in between was about me trying to create some distance. Both my parents were so creative and so principled, there was never really anything to rebel against – although my being gay felt like a kind of rebellion, because they were straight and happy and because there were no gay people in their lives. I came out to them when I was 21. I thought they already knew, but maybe they didn’t want to know. My father certainly reacted as though this was something I was deliberately doing to him, rather than something that was about me.

As a child I never ever felt I could be compelling enough for either of my parents to want to be around me all the time. I felt my mother’s work was a force in her life equal to motherhood. I never hated the work, but I deeply resented the time she spent away doing it. By the time I was eight she was spending two weeks at home and two weeks working in Pietrasanta. When I was ill she’d say: “If you don’t want me to go to Italy tomorrow, I won’t go.” And I’d say: “No, you must go because it’s important to you.” What I meant was: “Stay.” But she always went. Then, because I loved my mother so desperately, all my anger and resentment was directed at my father.

Work is my parents’ life, and it has always been an entirely fluid thing. My mother would give me a collage for my birthday and my father would write me a story. There weren’t any of the normal boundaries. And those boundaries are something my brother and I have been keen to have in our lives because our childhood felt so chaotic. There was no sense of routine: work, leisure and family were all wound into one. I don’t remember holidays – my parents didn’t take them. Recently, they came to stay with Henryk and me in the Caribbean, and after four days they were restless, my mother particularly. I understand it now. Part of her mind is permanently occupied with these forms she’s working on and needs to be engaged with.

We lived in a beautiful place, and that was a privilege, but money was something that was never discussed. There could have been plenty, there could have been none, I had no sense of where it came from, and that was quite scary. My parents’ values are around making a contribution to the world and leaving something behind. They’re not in the sphere of material gain and they don’t really understand the ephemeral world of TV. Becoming an entertainment reporter gave me this wonderful opiate of approval from thousands of people I didn’t even know. I think I deliberately went into the cultural gutter of reality TV so I wouldn’t look for approval from my parents or be disappointed when I didn’t get it. In fact, my mother is genuinely interested in what I do, because she’s fascinated by human communication. She simply reinterprets the subject matter and takes it to another, much more acceptable, level.

Mostly we talk about their work rather than mine – it’s always been a bit like that, but it’s not a problem any more. As a child I had a thing about not being good enough for my father. I projected that onto my life. I eventually turned it into “I’m going to be better than everyone”, which was a bit of a torturous racket. But there was a point in my thirties when I stopped holding my parents responsible for my happiness or unhappiness.

I’ve learnt a lot from my mother and father about what is really of value in life – it’s about who you love and who loves you. And I think they’ve learnt from me that life isn’t all about what you leave behind. My mother is particularly intuitive about relationships and the people in my life, so although she doesn’t really connect with the programmes I make, she is and always has been very involved in my journey.

HELAINE: I have a number of close women friends at the artists’ community where I work in Pietrasanta – and not one has children. Some aren’t even married, because they understand that the work is so intense, they couldn’t do both. I was really just beginning when Remy was born. Sculpture wasn’t then part of who I was. I wasn’t yet speaking through it, nor it through me. That happens slowly. Your emotions and your ability to convey them through your work gradually become one. It takes over and becomes a madness you can’t control.

I’d never been particularly interested in children and I was so worried about how motherhood would be; I was scared even to pick up Remy, he seemed so precious. Then, one day when he was about two months old, I was walking with the pram in the Bois de Boulogne and I had this incredible realisation: I’d never be lonely again and I’d never be able to be as moody and volatile. There was a recognition that this child was going to stabilise me, and he did. He released in me a sense of security I didn’t know I had. Remy was extraordinarily intuitive and in tune with where I was at. Even as a baby he could sense my mood. Far from making things difficult, initially motherhood enabled me to work anywhere. It made me realise that creativity wasn’t about uninterrupted time; it’s about having a state of mind that allows you to invest in what you’re doing.

The real struggle came later. Remy was five when Jared was born and he dictated a series of poems about how disappointed he was with this baby, but he was far more jealous of my work than he ever was of his little brother.

The summer he was seven and Jared two nearly killed me. I had so much energy for work and so many ideas to explore. I was getting up at 4.30am to go to the studio, I’d look after the children all day, then go back to my work. I was working on a big clay piece one day and Remy came in, took one of my sculpture tools, and attacked it. He said: “Mummy, I was talking to you and you didn’t even know I came in the room.”

For me, work is a conversation I can’t stop. It’s about letting go of your conscious side, entering layers and layers of your subconscious and feeding that into the material. I can work for 18 or 20 hours straight and not even be aware that time is passing. Shortly after the clay incident, Yorick and I decided I should spend more time in Pietrasanta, so I began working there for two weeks and coming home for two weeks. That became the pattern. I felt it was better. I’d arrive back with presents, so grateful I’d been given this time. It was only later I realised there was a price to be paid. A friend of mine asked Remy: “How did you really feel about your mother being a sculptor?” I’d never asked him that. And he said: “I didn’t think about her sculpture. I just felt abandoned.”

Remy was not an English schoolboy – he hated all sports and he had a very difficult time. He didn’t feel he fitted in, but how could he? As a family we’ve never fitted in, nor wanted to. In fact, we’ve always seen not fitting in as a virtue. The family unit was very powerful and we talked about everything. “What’s happening? How do you feel? What are your dreams?” We had those discussions at the table throughout his life. It was intense a little isolating. Remy was beautiful, understanding and sweet – he seemed so grown up, but I may have overestimated his ability to deal with things. I used to write him long letters from Italy describing my complex feelings, until he complained that it was overwhelming and he couldn’t handle it.

Growing up with two parents who were so idealistic must have been difficult. I was never part of the art mob; I did everything on my terms. It’s hard for a child to see the financial struggle and disappointment that went along with that. I know Remy feels the programmes he makes don’t please us. But that’s more to do with what he feels our expectations are. I loved Gay, Straight or Taken because it was so much about perception. Remy has enormous insight – when he was younger we thought he might be another Freud – and that’s why he’s been so successful.

I think I always understood he was gay without asking; by the time he was eight or nine I had a sense of it, but it never disturbed me – I see sexuality as a continuum. He believes in relationships: he’s only ever had two partners, and I’d be shocked if it was any other way. He grew up with us all having very strong relationships with each other and me with my sculpture. It’s what we think and talk about. I now go to him for advice – he’s so articulate and sensible and so very wise about people. I feel much closer to him than I ever did when he was a child. I do have regrets – there were difficult and painful times – but somehow these become your strengths as you grow older. I think we understand each other very well.

Helaine Blumenfeld’s work is on show at Robert Bowman Gallery, London SW1, from November 6. Tel: 020 7930 8003.

Photographs: Lydia Goldblatt